The Red Cedar River winds through the heart of campus and is a beloved spot for students, alumni and faculty alike. (MSU stock photo)

To Eric Tans, the Red Cedar River is at the core of MSU’s identity.

It’s a favorite running spot for the MSU environmental science librarian. Students sit by its banks to listen to the rushing water and watch the ducks swim by. Alumni return to take pictures by the waterfall. Faculty schedule walking meetings on the river’s tree-lined paths.

The river winding around MSU’s stately brick buildings is such an integral part of campus culture that it’s even in the opening lyrics to the school fight song. But at the same time, the iconic river is also misunderstood.

Tans was disheartened to hear students refer to the Red Cedar as “dirty.” Despite the river’s park-like setting, it’s known as polluted and unsafe. Tans believes that reputation is why too many people dump garbage, and even electric scooters, into the water.

If people understood the river, if they really knew it and were familiar with its history, Tans said, they’d be motivated to take care of it. He hopes his new story map detailing the Red Cedar’s long and varied history will do just that.

“To know the history of the water lets you understand where it’s been and how it’s been treated,” Tans said. “It strengthens the bond you feel. And when you know something really well, you want to take care of it.”

Tans recently debuted Close Beside the Winding Cedar, an online exhibit resulting from a six month-long research sabbatical. He combed through archived pictures and documents, listened to recordings and sorted through newspapers to piece together a thorough history of the Red Cedar River from its creation to the body of water the MSU community knows and loves today.

Since the exhibit debuted in July 2023, Tans has shared what he’s learned with the MSU community and beyond. He’s presented his findings in both academic and community settings and even shared the Red Cedar’s history in a walking river tour at this spring’s Science Festival. He’s exploring starting a podcast and looking for other ways to spread the Red Cedar’s history to the world.

Learning as you go

Tans got the idea for the project when a group of students contacted him during a research project on the Red Cedar dam, located in front of the administration building. They asked for his help with the history of the Red Cedar.

“I there would be a book on the shelf in the library all about the history of the river,” Tans said. “I looked for it, and it didn’t exist.”

While Tans is an information professional, he was more familiar with electronic databases and had no experience in archival research. Still, he was determined to learn. He signed up for a six-month mentoring program, where an MSU archivist and the head of special collections taught him how to conduct primary research and how to use the library’s archives. Then, he took a research sabbatical devoted to a deep dive into the Red Cedar River’s history.

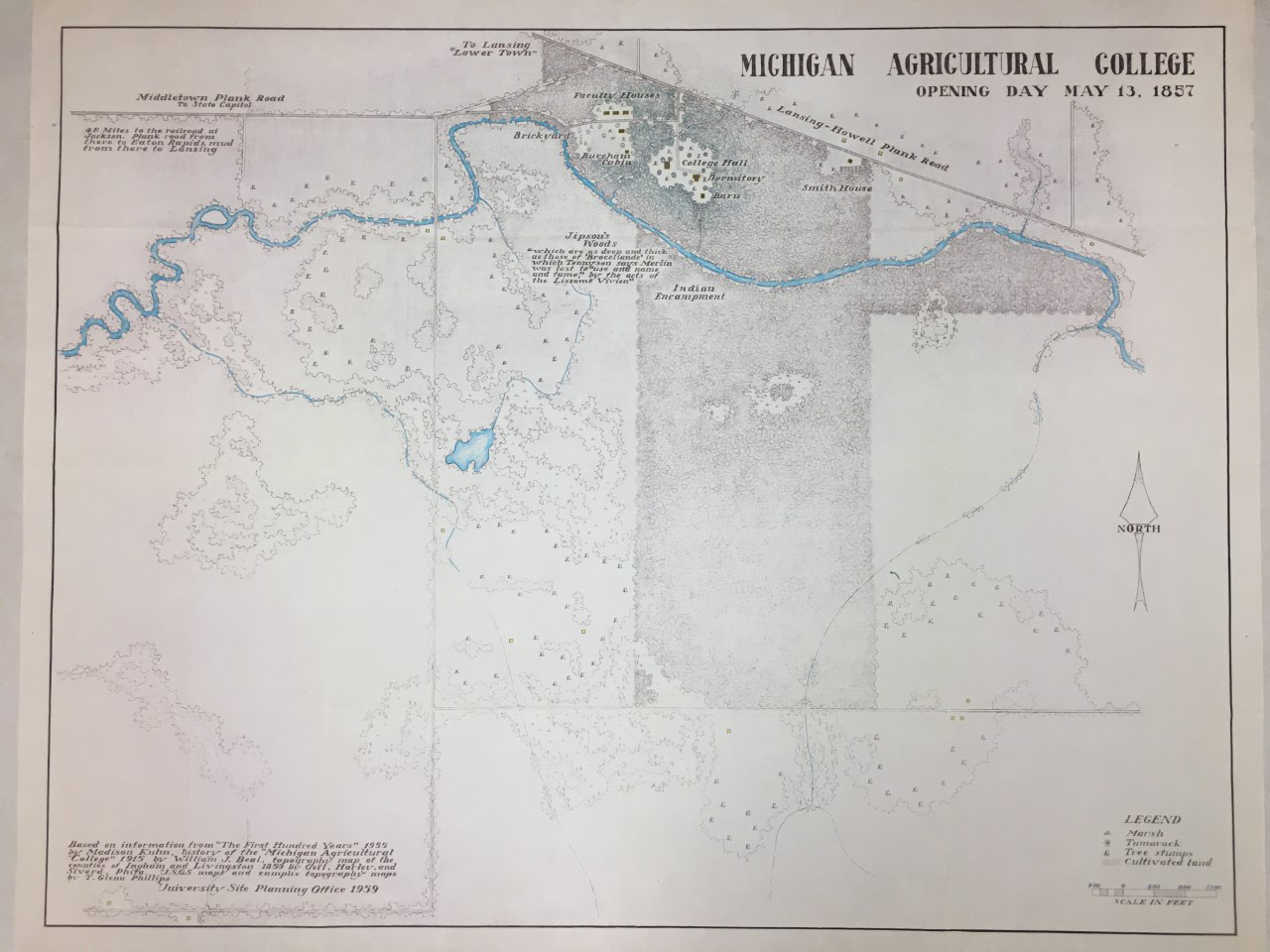

This map shows what the MSU campus would have looked like when classes began in 1857, including the brickyard where bricks for the first building would have been made and the “Indian Encampment” south of the Red Cedar River. (Photo courtesy of MSU Archives and Historical Collections)

Tans’ days were spent browsing resources that had been digitized and submitting requests for materials. He sat in the library’s Special Collections Reading Room sorting through piles of paper, looking for nuggets of information gold. He set aside anything that looked even remotely related to the Red Cedar. When he found something useful, he took a picture with his phone. He wrote copious notes to track what he found and pull it together in a way that made sense.

A storied history

Long before MSU existed, the East Lansing area was covered with glaciers hundreds of feet thick. When the glacier retreated, it carved the river channel that filled with water and became the river of today. Flowing east to west, the Red Cedar was part of a network of rivers and land trails that the local Anishinaabeg people used for transportation and trade.

East Lansing was a seasonal encampment, where villages of Native Americans harvested sugar maples, hunted, fished and grew crops during warm months. They moved on each winter until it was time for the sugar maple harvest again.

The 1819 Treaty of Saginaw changed everything. Under the treaty, the U.S. government owned the land where MSU now resides, while the tribes could still hunt and fish. Then, under the Indian Removal Act, the government rounded up the Native American people and sent them to reservations.

While Tans knew this was part of U.S. history, seeing it so starkly written in print was difficult.

“It’s a dark chapter in American history,” Tans said. “What is the right way to honor that history without being flippant? But I think one of the most important things you can do is tell the history.”

What Tans hadn’t expected was that many people escaped the fate of being sent to reservations out west. They hid in the woods and moved up and down the river, living the nomadic lifestyle traditional to their people. Tans found reports early in MSU’s existence of students spotting people camping by the river and hunting. Even today, descendants of those tribes remain in the East Lansing area. They are still here, Tans said, and they have always been here.

Industrial riverfront

The river planed a key role in MSU’s construction. The red bricks from campus’s earliest buildings were made from sand and clay harvested from the riverbanks. All buildings that were heated by boilers pumped water from the Red Cedar to keep the boilers going.

“This school wouldn’t exist without the river,” Tans said.

Because the river was being used as a tool, it had none of the natural beauty that it does today. No vegetation or trees lined the river at all next to the MSU power plant, allowing for easy access to use for campus facilities.

Tans also learned that the Red Cedar’s polluted reputation has a historical background. When MSU was first built, the pipes and toilets flushed untreated human waste into the river. This was common at the time, as wastewater treatment hadn’t been developed yet.

The campus’s first wastewater treatment facility was built in the 1920s, but by the time it was finished, MSU’s student population had exploded, and the facility didn’t have the capacity to meet the demand. It wasn’t until the East Lansing wastewater treatment facility was built in the mid-1960s that human waste stopped flowing into the river. Then, the Clean Water Act of 1972 mandated that facilities stop overflowing into rivers.

The Red Cedar riverfront was once an industrial area, barely resembling the park-like environment it boasts today. “Photo courtesy of MSU Archives and Historical Collections)

In time, the river recovered. Aquatic plants took in nutrients from human waste, while bacteria diluted over time. MSU leaders began efforts to restore the area around the river in the 1940s. They learned to appreciate the river and declared it a sacred space, and gardens and trees were planted to accentuate its beauty. Meanwhile, the river remained a hub of student activity, with traditions going back to the university’s founding.

Still at risk

Today, one of the biggest risks facing the Red Cedar is trash dumping. So many abandoned electric scooters have been found in the river the City of East Lansing revoked its contract one scooter company earlier this year. Scooters are especially a risk because the lithium from their batteries can leach into the water.

Tans hopes that as more people view his exhibit and learn about the Red Cedar’s history, they’ll be motivated to care for it and change problem behaviors. Keeping the river clean and safe is crucial to ensuring students and faculty can continue to enjoy the Red Cedar for years to come.